Sixteen months ago, Brigham Young University and Steven Jones parted ways, but he said this week he isn't bitter about the academic divorce.

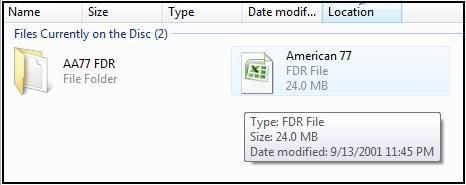

He certainly hasn't curtailed his volatile research on the collapse of the three World Trade Center towers after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

(Yes, three towers fell, not just two. If you didn't know that, Jones is particularly interested in reaching you with his message that some other group, in addition to al-Qaida, likely contributed to the collapses.)

In fact, Jones is the lead author of a paper on the collapses published April 18 in a civil engineering journal.

The journal article does not list his past tie to BYU, and that's a big Mission Accomplished for university leaders, who felt they acted to protect BYU's reputation when they worked out a retirement package with Jones and he left at the end of 2006.

But Jones is sharing a cramped BYU office with some professors. He also does research in a BYU lab as an outside user with a student who works with him.

Most importantly, he is preparing several more papers that, if they pass peer review and are published, will give him the peace of mind that his case reached the public.

Jones was energized in November when he and others received a response from the national lab charged by Congress to determine why and how the towers collapsed. The letter contained the following phrase:

"We are unable to provide a full explanation of the total collapse."

"That," Jones said, "really was progress. It made me believe we could talk with them."

It is striking. After producing a 10,000-page report, the National Institute of Standards and Technology can't explain the collapse. And on its Web site, NIST clearly states that nowhere in its report did it say that steel in the Twin Towers melted due to fires. In fact, the fires reached only 1,000 degrees Celsius. Steel melts at 1,500 degrees Celsius.

Meanwhile, the Federal Emergency Management Agency has said that its best hypothesis for the fall of the third tower, WTC 7 — diesel fuel stored in the building caused fires that collapsed the building — has a "low probability" of being correct.

At the time of his separation with BYU, which he admitted was painful, Jones found himself burned by his association with a loose confederation of 9/11 truth-seekers, some of them clearly kooky conspiracy theorists, and by some of his own statements.

Now, he and a number of scientific colleagues are taking a more cautious, mainstream approach.

His new peer-reviewed paper in the Open Civil Engineering Journal doesn't rip NIST or FEMA or the government. It does just the opposite. It lays out 14 points of agreement Jones and his colleagues have with the official government reports.

"We're getting to a higher level of discussion with this paper," Jones said.

The open paper can be found for free on the Web at www.bentham.org.

So what does Jones think happened?

Jones wants NIST to look at new evidence he found in Ground Zero dust samples since leaving BYU. The dust is full of iron-rich spheres and red-gray chips with the chemical signatures of high-tech cutter-charge explosives that he said could explain the collapsed towers. The spheres come from molten metal that Jones said could be caused by cutter charges.

"It's like when you spray water into the air, you get droplets," Jones said. "These spheres are evidence of extremely high temperatures beyond what the fires could have reached."

He's offered samples to NIST and invited NIST to visit one of his group's labs. A NIST spokesman has said that would be a waste of taxpayer dollars, though Jones said the cost would be less than $5,000.

Jones is cautious with money himself. He and his wife are selling off their real-estate investments to make ends meet, but he said they are comfortable and about to move to Sanpete County.

"I haven't profited a penny off this," he said. "I don't want to, and I've been careful not to. I'm concerned about the country, and I'm worried the truth is being covered up here."

He's careful not to speculate about a cover-up, though he said the growing dissatisfaction with the war in Iraq has made many more people receptive to his research.

Would it really hurt the people at NIST to talk to him once?

Source

New York State health officials have released statistics indicating that 360 9/11 rescue workers have since died, but have also admitted that there is an overall undercount.

New York State health officials have released statistics indicating that 360 9/11 rescue workers have since died, but have also admitted that there is an overall undercount.